Amy Coney Barrett Surprised By History Of Cross-Dressing Laws Targeting Trans People

The justice is a potential wild card in the recent Skrimetti case around transgender rights.

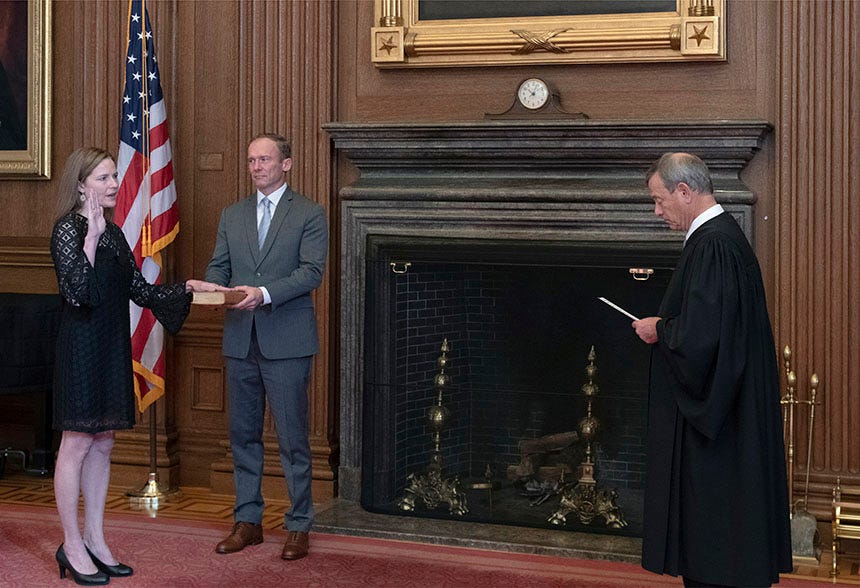

Today's Supreme Court hearing in United States v. Skrmetti was historic, featuring Chase Strangio as the first openly transgender attorney to present arguments before the Court. Strangio's advocacy was both impactful and insightful, addressing justices who hold the future of equal protection for transgender individuals in their hands. The case challenges Tennessee's ban on gender-affirming care for trans youth, and also will determine if transgender people can be legally discriminated against. Reactions to the oral arguments have been mixed, with some expressing pessimism about the prospects for transgender rights. However, a notable moment occurred when Justice Amy Coney Barrett appeared surprised to learn about the historical de jure discrimination against transgender individuals through anti-crossdressing laws, suggesting she could be a potential wild card in the eventual ruling.

The topic first arose when Justice Barrett posed a question to Solicitor General Prelogar regarding historical de jure discrimination against transgender people. Barrett asked, “You point out in your brief that in the last three years there have been these laws, but before that, we might have had private societal discrimination. However, I don’t know of any instances—am I missing something? Is there a history that I’m unaware of where we have de jure discrimination?”

Several minutes later, Justice Samuel Alito questioned Chase Strangio, expressing skepticism that transgender people could be granted quasi-suspect classification—a legal designation that would subject laws affecting them to heightened scrutiny—due to what he saw as a lack of historical legal discrimination, to which Strangio replied that such historical discrimination existed legally in two places: the military and in anti-crossdressing laws.

The latter appeared to take Justice Barrett by surprise, something that she would return to a few times during her oral arguments. In a follow-up line of questioning towards Strangio, Barrett admitted that she never knew about the long history of cross-dressing laws, indicating that she may be convinced by Strangio that de jure legal discrimination was indeed part of transgender legal history.

“Mr. Strangio, I wanted to give you a chance to clarify. I’m not sure if you named all the laws when we were discussing de jure discrimination earlier. You mentioned bans on cross-dressing and bans on military service. I had thought of the military service ban, but I wasn’t aware of statutes prohibiting cross-dressing. Can you think of any others?” She asked, her tone indicating surprise.

To which Strangio replied, “I would say there are other examples where homosexuality and transgender status are sometimes grouped together in discriminatory frameworks as language has evolved. However, I think the most salient examples would be the cross-dressing bans and the explicit bans on military service.”

She would return to the question again when asking the Tennessee Soliciter General Matt Rice if he had any response, “I was asking your colleagues on the other side about de jure discrimination and what factors we should consider when determining whether transgender people should be recognized as a suspect class under the Fourteenth Amendment. Do you have a response?”

Rice indicated that he had no knowledge of de jure discrimination.

Cross-dressing laws have long been used to target the transgender community. The first such laws appeared in 1843, prohibiting individuals from “wearing the apparel of the other sex.” These laws became tools of enforcement during police raids in the 1960s, particularly around the time of the Stonewall riots. Responding to Justice Barrett’s questioning on social media, the ACLU’s Gillian Branstetter highlighted a 1964 case challenging a cross-dressing law, quoting a newspaper report on the defense: "The defense submitted by the ACLU contends that it is unconstitutional to arrest as a vagrant a transvestite who has done nothing more than wear the clothing of the opposite sex."

Attorneys working on other LGBTQ+-related cases have privately shared intrigue over Justice Barrett’s questioning, with one expressing “surprising hope” about her potential stance on the case. During other portions of the hearing, Chase Strangio appealed to Barrett’s previous rulings on COVID-related cases, where she acknowledged that medical care could intersect with equal protection issues, particularly in the context of religious services. Barrett also gave Strangio an opportunity to discuss the political powerlessness of transgender people amid recent waves of anti-trans legislation—a point Justice Sotomayor later underscored in questioning Tennessee’s attorney. Sotomayor remarked, “When you are less than 1% of the population, it’s very hard to see how the democratic process is going to protect you.” Collectively, her discussion could make her a potential swing vote in the case.

It is also important to note that Justice Barrett has recently sided with liberals in choosing not to hear major cases on LGBTQ+ rights. Justice Barrett refused to reinstate Florida’s drag ban in November of 2023. She also refused to hear an appeal on Washington’s conversion therapy ban, allowing it to stand and joining Roberts and Gorsuch along with the liberals in that decision.

The outcome of this case carries immense weight for transgender rights, with many legal experts predicting the Court may lean towards upholding the Tennessee ban. However, it’s worth remembering that this same Court (minus Barrett, + Ginsburg) delivered the landmark Bostock decision, which protected transgender people from workplace discrimination using similar legal principles. As the nation awaits the ruling, likely to come early this summer, transgender people and their allies hold onto hope that at least two conservative justices will recognize the gravity of the case and join in affirming the fundamental rights of one of the country’s most vulnerable communities.

The full Supreme Court transcript may be found here.

Correction: A previous version said the same court approved Bostock. Ginsburg was on that decision, and Barrett was not.

After reading through the oral arguments, Barrett's question also stuck out to me. The other was the implicit bias is some questions that transgender people are lesser and care should be banned for all just in case a cis person transitions. The other was that stupid 85% detransition statistic coming up as a rational fact, when it's simply not true.

I did enjoy seeing Rice get ripped apart in the early questioning, which was nice.

I think the underlying context of the case though was the immutability of being transgender. Rice basically was saying it is a mental condition (without saying it), and I think Kavanaugh tried to undermine immutability by saying someone who detransitions proves it's changeable (while not saying the same about someone who never detransitions). I think it is this point which underlies a lot of the attacks on our rights, many people think it is a choice. From my reading that seems to be the area which requires a concerted effort on our part, and could help undermine a lot of the hate campaign and moral panic.

While I suppose it’s good to inject a bit of optimism in this, as a matter of reality I feel like this case was already decided before the first arguments were even heard. In fact, given the current composition of the court, bringing the case before SCOTUS may end up doing more harm than good. The justices will very likely uphold the Tennessee ban 5-4 or 6-3, thus returning the issue to the states. By itself that wouldn’t be the worst possible outcome, since GAC would still be available in the blue states. The problem is that such a ruling would embolden the Trump administration to try to ban GAC nationwide - adults as well as minors. That would set up a classic feds. vs states rights clash, as GAC access is written into the constitutions of several blue states.